by: Caitlyn Carrillo

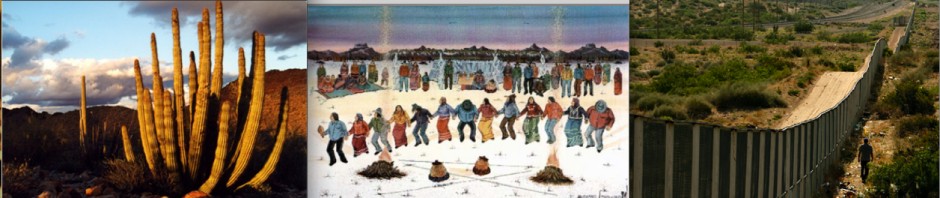

The visitor experience to Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument has been shaped by two factors: time and place. These factors have interacted to create a visitor experience that is different than a trip to any other national monument or park. A trip to Organ Pipe after its founding in the late 1930s would have been completely different than what park visitors experience today. Visitors experiences can also vary based on the race, social class, or citizenship status of the visitor. This shift has occurred because of changes within the administration of the larger National Park Service structure. More specifically to Organ Pipe, the monument is affected by the ever-increasing role the United States-Mexico border has played on the management of the monument site. Because the monument’s southern boundary is also an international border, the management structure of the park is not only a concern for the National Park Service, but also Home Land Security.

A trip to Organ Pipe after its founding in the late 1930s would have been completely different than what park visitors experience today. Visitors experiences can also vary based on the race, social class, or citizenship status of the visitor. This shift has occurred because of changes within the administration of the larger National Park Service structure. More specifically to Organ Pipe, the monument is affected by the ever-increasing role the United States-Mexico border has played on the management of the monument site. Because the monument’s southern boundary is also an international border, the management structure of the park is not only a concern for the National Park Service, but also Home Land Security.

The National Park Service’s 1941 master plan for Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument detailed how officials envisioned visitors would experience the area and how it would be managed. At the time, there was no satisfactory record of seasonal attendance to the monument. However, the monument management expected that the heaviest travel would occur in the winter months due to the extreme heat prevalent in the summer months.[1] In addition, the Organ Pipe area was not well-known by the public outside the region, but planners expected it to become a popular tourist attraction for visitors from the east coast. Tourists to the area were restricted to predetermined portions of the monument in which interpretive programs were already developed.[2]

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the NPS budget was sliced in half. By 1942 the Civilian Conservation Corps had been terminated. This is significant because the CCC aided in maintaining park and monument sites like Organ Pipe. In the crisis of war, however, the country needed men to fight abroad, not maintain trails in its national parks. In addition, prior to America’s involvement in the war the Park Service had a permanent staff of 5,963. By June of 1944, the staff had dwindled to 1,573. The war also diminished park visitation. Rubber shortages and the rationing of gasoline made it difficult for visitors to reach the national parks. Thus, the national parks fell into disrepair. The lack of manpower and visitation crippled the national parks. [3]

After World War Two, visitation to national parks and monuments spiked. Starting in the 1960s and moving into the 1970s a shift occurred in the administration and management of the national parks. Under director Conrad Wirth, a plan to revitalize the national parks was set into motion. This plan to make over the parks was dubbed Mission 66. As if trying to make up for the war-time neglect of the parks the government invested about one billion dollars into the parks between 1956 and 1966. It took ten years to recover what had been lost in five. The main objective of Mission 66 was to rebuild the infrastructure of the national parks.[4] This included the building of visitor centers, as well as the improvement of roads and trails. Wirth’s thought was that if visitors were going to use certain areas, the Park Service should prepare for this. In addition, the new facilities were built-in a way that they “would limit the impact to specified areas.” [5]

Not only did Mission 66 pull the national parks out of their funk but it also paved the way for future management practices. With improved infrastructure the parks became more accessible to the public. Gone was the desire to restrict the area of our national parks from the 1930s and 1940s. Instead, land could not be preserved fast enough. In 1965 alone, fourteen new parks were created. This trend only continued as the years went by. Towards the close of the Mission 66 in 1966, annual visitation to the parks reached about 133.1 million.[6] During the Mission 66 era, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument produced a guide which led drivers along various routes through the park’s Ajo Mountains.[7] Visitor guides were also produced. These guides highlighted the history, plant and animal life, and various attractions visitors would be able to see and experience within the monument site.[8]

Visitors to Organ Pipe today can experience much of the same things that visitors could in the 1960s. As a border park, however, the monument has come under stress in recent years. In the mid-1990s, the U.S. launched its “war on drugs” and also attempted to reduce illegal immigration.[9] This crack down on the border directly affected border parks including Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. In a 24-hour period during peak migration months, close to one thousand immigrants traverse through Organ Pipe.[10] Authors Carol Ann Bassett and Margaret Regan, illustrate two ways in which Organ Pipe is be experienced today. In Organ Pipe: Life on the Edge, Bassett makes Organ Pipe come alive. “A dozen cone-shaped figures jut sharply from the earth,” she writes of Bull Pasture. They look like wizards’ hats. A rock formation called the Sphinx stands nearby, and serrated ridges rise like the backbone of a stegosaurus.”[11] With such descriptions, Bassett brings readers right into the park to join her exploration of the landscape. Bassett’s experience focuses on the solitude and beauty of her surroundings. But, other visitors at the same time and in the same place had radically different experiences.

“A dozen cone-shaped figures jut sharply from the earth,” she writes of Bull Pasture. They look like wizards’ hats. A rock formation called the Sphinx stands nearby, and serrated ridges rise like the backbone of a stegosaurus.”[11] With such descriptions, Bassett brings readers right into the park to join her exploration of the landscape. Bassett’s experience focuses on the solitude and beauty of her surroundings. But, other visitors at the same time and in the same place had radically different experiences.

Margaret Regan chooses a different story to tell in her book, The Death of Josseline: Immigration Stories From the Arizona Borderlands. Full of stories from illegal immigrants and rangers and border patrol officials Regan’s book conveys the risks of traveling through the desert of Organ Pipe. The migrants sojourns in Organ Pipe arise more from necessity than recreation. Most illegal immigrants are trying to reach family already in the states or are entering the U.S. to become more economically stable. Josseline’s story, in particular, rends readers’ hearts. While on her way to Los Angeles, fourteen year old Josseline became very ill trekking through the Sonoran Desert. It was her responsibility to make sure that she got her little brother and herself to their mother. Josseline never made it. She is just one of hundreds to die every year in the area over the last decade.[12]

Full of stories from illegal immigrants and rangers and border patrol officials Regan’s book conveys the risks of traveling through the desert of Organ Pipe. The migrants sojourns in Organ Pipe arise more from necessity than recreation. Most illegal immigrants are trying to reach family already in the states or are entering the U.S. to become more economically stable. Josseline’s story, in particular, rends readers’ hearts. While on her way to Los Angeles, fourteen year old Josseline became very ill trekking through the Sonoran Desert. It was her responsibility to make sure that she got her little brother and herself to their mother. Josseline never made it. She is just one of hundreds to die every year in the area over the last decade.[12]

Bassett’s landscape and Josseline’s are the same, but these two visitors had completely different experiences. Where Bassett appreciates the nature and the history that surrounded her in Organ Pipe, immigrants like Josseline experience tribulation. These differing narratives reflect the differing views surrounding this monument area. One view is focused on individual recreational enjoyment, while the other is focused on a harrowing trip that is made out of necessity. Both time and place have shaped Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument into what it is today. World War II had detrimental effects on the entire park system, but through Mission 66 national parks were revitalized. Interpretive programs and driving trails were established during the Mission 66 era in Organ Pipe. As time has progressed, Organ Pipe’s location has shifted how visitors experience the park. As Josseline tragically indicates, visitors’ immigration status also shapes visitors’ experience as much as time and place.

[1] “Interpretational Development Plan for Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument,” n.d., 600-01 Organ Pipe, box 218, C1-NARARMR.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Richard West Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 150-51.

[4] Ibid., 149.

[5] Ibid., 181.

[6] Richard West Sellars, Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

[7] “Organ Pipe Cactus national Monument Driving Guide,” K3819- a/b.1, 1956-1958, ORPI, Box no.10 GC 53-58-NARARMR.

[8] United States Department of the Interior, “Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument,” 1957 Leaflet, K3819- a/b.1, 1956-1958, ORPI, Box no.10 GC 53-58-NARARMR.

[9] Chris Nielsen, “Illegal Immigrants Bring Problems to Border Parks.” School of Communication. University of Miami. http://www.ournationalparks.us/index.php/site/story_issues/illegal_immigrants_bring_problems_to_border_parks/ (accessed April 16, 2012).

[10] Ibib.

[11] Carol Ann Bassett, Organ Pipe: Life on the Edge (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2004), 8.

[12] Margaret Regan, The Death of Josseline: Immigration Stories from the Arizona Borderlands (Boston: Massachusetts, Beacon Press, 2010), ix-xvii.