by Gage Patinella

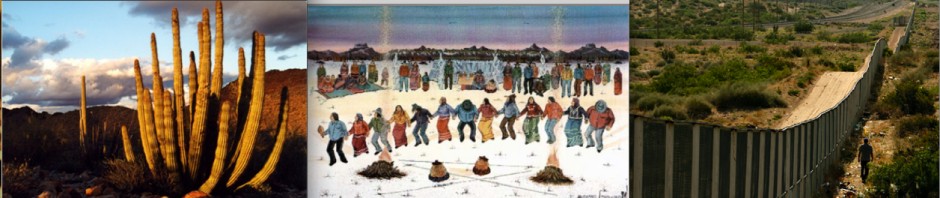

While the first half of the history of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument was filled with controversy over what to do about grazing and mining claims, the period ranging from 1976 until the present has been filled with much less controversy and far more scientific interest. By 1976 the last of the Gray family, who had ranched upon lands within the boundaries of the monument for more than fifty years, had passed away effectively ending the era of grazing within Organ Pipe National Monument. Similarly, in 1976, the 1941 Act of Congress allowing for mining and prospecting within park boundaries was repealed. Intense criticism and heat from environmentalists during the late 1960s and 1970s helped to rid the park of its mining and grazing problems. During this time civilians and environmentalists began to witness Organ Pipe for what it truly was, a diverse desert environment inhabited by unique plants and animals not found anywhere else on earth, an environment they believed needed to be protected.

The 1970s entailed a decade full of scientific interest in and around the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument area. By 1975 all the cattle had been removed from the monument in hopes of restoring the park to the beautiful desert environment it was prior to European contact. On October 26, 1976, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument was designated an International Biosphere Reserve. International Biosphere Reserves are projects of the Man and the Biosphere program of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Each reserve is a protected sample of the world’s major ecosystem types. These sites are standards against which we can measure human impact on our environment and predict its probable effects. There are now over 190 reserves in 50 countries.[1] Likewise, on October 26, 1976, Congress designated ninety-five percent of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument lands as wilderness. Wilderness lands are “semi-pristine lands, lands with no roads or no permanent structures, areas where Man is a visitor who does not remain.”[2] These various Acts passed by both an international governing body, UNESCO, as well as the U.S. federal government, showed how the metaphorical tides had begun to turn within the monument itself. The economic sectors of ranching and mining had been dismissed making room for scientific investigations into the fragile ecosystem that is the Sonoran Desert. The National Park Service itself began to notice the attention being drawn from Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, and decided to help preserve this unique ecosystem. In 1978 the National Park Service placed Quitobaquito Springs and its surrounding area onto its National Register of Historic Places. The National Register of Historic Places is the official list of the nation’s historic places worthy of preservation. The National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America’s historic and archeological resources.[3]

During the 1980s little action was seen within and around the area surrounding Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Scientific research was being gathered and executed, while the citizens of America were able to enjoy the desert landscape that makes up the monument. However, during the 1990s, a shift began to take place. During this decade illegal immigration began to increase dramatically, which paralleled the increase in drug trafficking witnessed with in the monuments boundaries.[4] The efforts to curb illegal immigration and drug smuggling in the larger urban areas such as El Paso and San Diego caused immigrants and drug smugglers to look for other access points into the United States. One of the points of entry found was the southern border of the monument. As mentioned above, ninety-five percent of the monument became designated wilderness without roads and often without people, making the monument the perfect point of entry for hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants. Their numbers steadily increased over the next decade, where it is estimated that in the year 2000, some 200,000 illegal immigrants crossed into the United States through Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.[5]

Not only did these illegal immigrants bring drugs with them across the border, they also brought a world of violence. In 2002, while chasing down a suspected illegal drug trafficker, Park Ranger Kris Eggle was shot and killed in the line of duty. It is with this newfound duty of patrolling for illegal immigrants and drug traffickers, which park rangers are faced with on a daily basis that has caused Thomas Clynes to dub Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument “America’s most Dangerous Park.” On November 22, 2003, by Congressional Act, the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument Visitor center was renamed in honor of Kris Eggle.[6] Due to the large number of illegal immigrants crossing into the monument annually, the National Park Service decided in 2004 to begin construction on a vehicle barrier lining the thirty-three miles of international border the monument shared with Mexico.[7] It took two years, but in 2006 the vehicle barrier along the U.S.-Mexico was completed, drastically reducing the number of vehicles entering the park illegally.

[1] National Park Service, “Monument Designation: Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument,” National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/orpi/parknews/prkit-designation.htm (accessed April 17, 2012).

[2] Ibid.

[3] National Park Service, “National Register of Historic Places,” National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/nr/ (accessed April 17, 2012).

[4] National Park Service, “Monument Timeline: Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument,” National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/orpi/history/culture/monument-timeline.htm (accessed April 16, 2012).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.