by Josie Kohnert

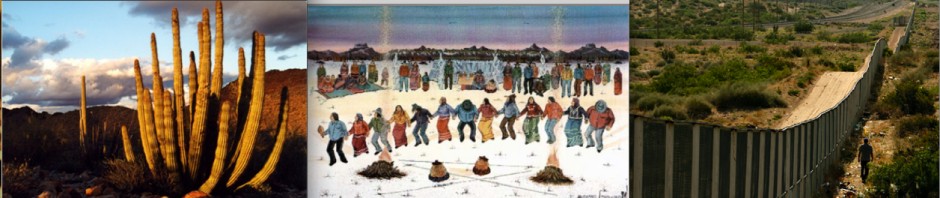

Located a mere two hundred yards from the U.S.-Mexican border, Quitobaquito Springs provides an oasis in the harsh surrounding Sonoran landscape. As one of the few reliable sources of water found within Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, it provides visitors with a record of both ecological and human activity.

The water originates from a fault in the granite-gneiss cliffs of the adjacent hills; a fault that pushes up deep water by creating internal cracks[1]. It then runs through a series of small ditches and culminates in a shallow pool known as Quitobaquito Oasis. For many animal species—such as the endangered Quitobaquito Pupfish and Sonoran Mud Turtle—the springs are an essential component of life in the desert. The Pupfish thrives on the algae covering the bottom of the pond and is the source of a great deal of scientific study. The desert springs, however, are extremely fragile ecosystems, and the riparian habitat that depends on the springs is constantly threatened by water diversion, habitat destruction, and exotic species introduction[2] resulting from human use.

Despite the ecological fragility, the springs have persisted through centuries of human habitation. Various cultures across history used the stable water body to establish permanent settlements. As a result Quitobaquito Springs contains remnants of one of the oldest human settlements in the monument. Archeological evidence found on site demonstrates that the springs were a territorial marker between two linguistic groups of

Tohono peoples, and had ceremonial significance as well.[3] The first European thought to visit Quitobaquito was the Spanish Jesuit priest Eusebio Kino in 1698, and since that time the springs remained a popular stop between Sonoyta and Yuma on the Camino del Diablo.[4] Visitors to the springs ranged between Spanish, Sand Papago, Anglo, and Mexican from 1698 onward. Since then, it has been used for a variety of purposes, even manipulated to support farming in the region. The Spanish documented evidence of agriculture near the springs in 1774, and in roughly 1860, American farmer Andrew Dorsey settled in the region. He expanded the pond, built a dam, and grew a variety of produce including pomegranates and figs. Currently, the National Parks Service is working to properly manage and preserve this valuable cultural and ecological resource.

Further Reading

Anderson, Keith M., et. al., “Quitobaquito: A Sand Papago Cemetery” Kiva , Vol. 47, No. 4 (Summer, 1982): 215-237, http://0-www.jstor.org.catalog.library.colostate.edu/stable/30247343 (accessed February 10, 2012).

Cole, Gerald A., and Melbourne C. Whiteside, “An Ecological Reconnaissance of Quitobaquito Spring, Arizona,” Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science , Vol. 3, No. 3 (Apr., 1965): 159-163, http://www.jstor.org.catalog.library.colostate.edu/stable/40022769 (accessed February 10, 2012).

Cox, Thomas J., “The Food Habits of the Desert Pupfish (Cyprinodon macularius) in Quitobaquito Springs, Organ Pipe National Monument, Arizona,” Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science , Vol. 7, No. 1 (Feb., 1972): 25-27, : http://0-www.jstor.org.catalog.library.colostate.edu/stable/40024362 (accessed February 10, 2012).

Hoy, Wilton E., “A Quest for the Meaning of Quitobaquito,” Kiva , Vol. 34, No. 4 (Apr., 1969): 213-218, http://0-www.jstor.org.catalog.library.colostate.edu/stable/30247091 (accessed February 10, 2012).

Kodric-Brown, Astrid, and James H. Brown, “Native Fishes, Exotic Mammals, and the Conservation of Desert Springs,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment , Vol. 5, No. 10 (Dec., 2007): 549-553, http://0-www.jstor.org.catalog.library.colostate.edu/stable/20440767 (accessed February 10, 2012).

[1]Gerald A. Cole and Melbourne C. Whiteside, “An Ecological Reconnaissance of Quitobaquito Spring, Arizona,” Journal of the Arizona Academy of Science , Vol. 3, No. 3 (Apr., 1965): 159-163, http://www.jstor.org.catalog.library.colostate.edu/stable/40022769 (accessed February 10, 2012).

[2] Astrid Kodric-Brown and James H. Brown, “Native Fishes, Exotic Mammals, and the Conservation of Desert Springs,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment , Vol. 5, No. 10 (Dec., 2007): 549-553, http://0-www.jstor.org.catalog.library.colostate.edu/stable/20440767 (accessed February 10, 2012).

[3]Keith M. Anderson, et. al., “Quitobaquito: A Sand Papago Cemetery” Kiva , Vol. 47, No. 4 (Summer, 1982): 215-237, http://0-www.jstor.org.catalog.library.colostate.edu/stable/30247343 (accessed February 10, 2012).

[4] Wilton E. Hoy, “A Quest for the Meaning of Quitobaquito,” Kiva , Vol. 34, No. 4 (Apr., 1969): 213-218, http://0-www.jstor.org.catalog.library.colostate.edu/stable/30247091 (accessed February 10, 2012).